THE SWEET REVOLUTIONARY

Debussy is one of the most significant composers of what is called the “late romantic” period, and one of the founders of what is called “modernism”, in Western Art Music. His influence runs very deep, but is quite hard to define. Famously, he did not want imitators. He was uncomfortable with fame. His music was not violently rhythmic like the Rite of Spring, nor was it challenging to listen to like Pierrot Lunaire. In fact, his music was beautiful, often sensuous, but always direct, evocative, colourful. Also, he was militantly opposed to the conservatoire and academic music. In exasperation at the musical rule-givers Debussy cries: “music cannot be learned!”

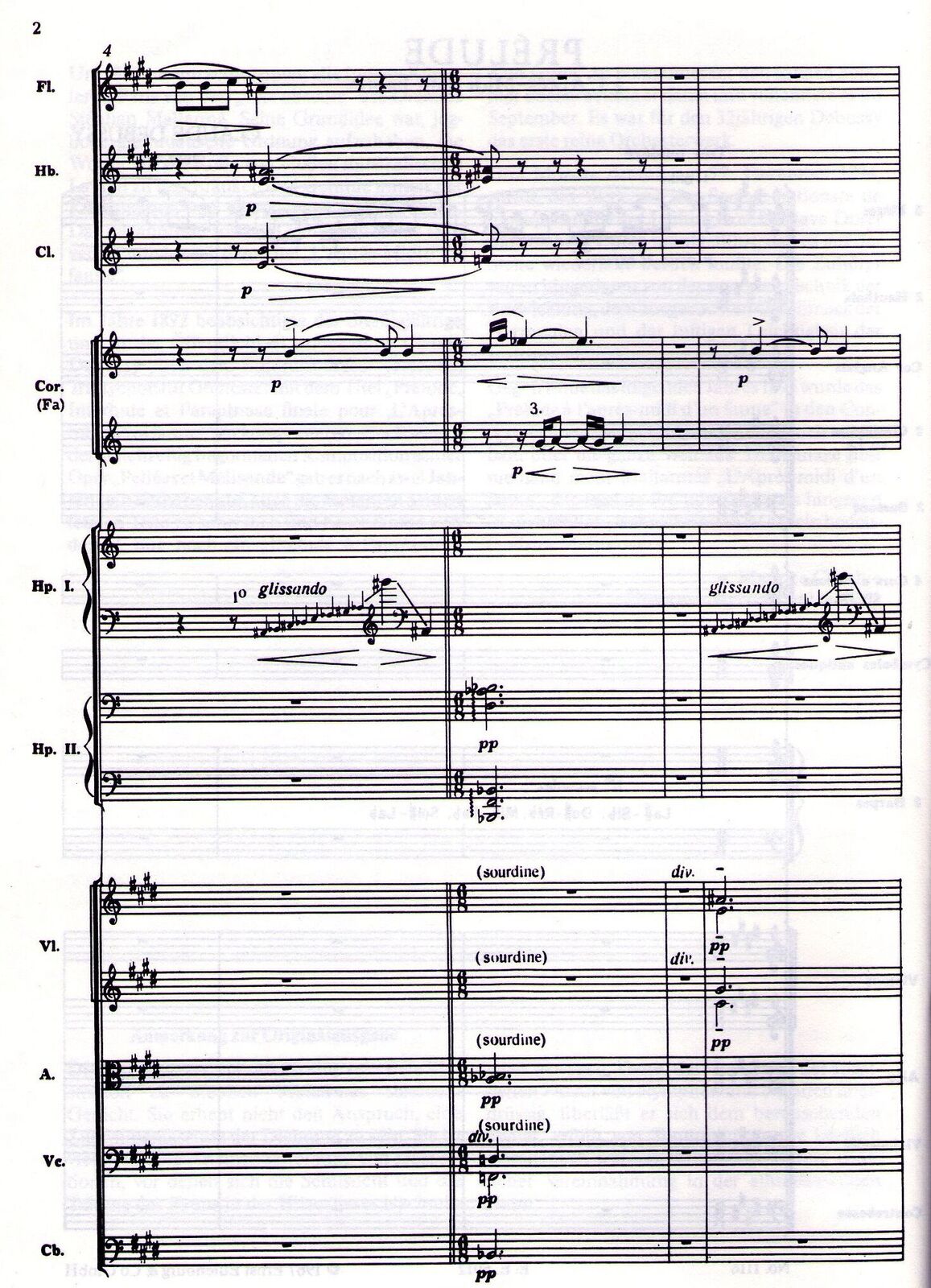

One of Debussy’s most popular works, the orchestral piece L’Apres-Midi d’une Faun, is a perfect example of the manner of Debussy’s revolution. The ambiguity of the opening unaccompanied flute passage - it does not belong in any particular key; it floats in unmeasured rhythm; it’s melodic contours wander chromatically in melancholic whimsy

– the sustained unmeasured feel of the rhythm even once the orchestra joins the soloist – the continually unresolved harmony: the long notes of the melody reharmonised, never quite settling until the very end of the piece – all of these speak of a revolution in how music can be conceived, how melody can be freed from harmonic constraints, how harmony can be fleeting, momentary, freed from the requirement to resolve, and how rhythm can be dissolved from the four-beat four-bar grid.

In Debussy’s time Wagner was the ubiquitous force in music. If a composer wanted to write an opera – the equivalent of today’s feature film in many ways – it was called a “wagneriana”. Many composers felt the need to emulate him, to adopt his style and sound. Many reacted against his dominance, however. The problem for them was how to break free. Schoenberg took his music in an Expressionist direction, writing of warped

emotions and madness. Eric Satie turned away from grand themes and gestures, concentrating on miniatures and Dada-like silliness ( with performance instructions like “Arm yourself with clairvoyance”); his music, with its repetitions and apparent simplicity is prescient of the minimalism of 1960s and later. Some composers turned to Nationalism, looking to folk song and folk tale for inspiration. Some turned to the music of the past, becoming neo-classicists, neo- baroquists, etc.

Debussy did something different. He has been called an Impressionist – because his music often refers to natural phenomena like clouds, the sea, and so on, and because his music is often suffused with washes of sonority and colour – but this would be to misunderstand Debussy’s impressionism. What Debussy did was to encounter some phenomenon – clouds, the sea, but also a poem, a legend, a crowded park on a Sunday afternoon, a firework display, a picture postcard of a mysterious archway in the Al Hambra in Spain, a Javanese Gamelan orchestra at the Paris Exhibition – to savour the encounter, to allow the phenomenon to have some impression upon him, explore it and his own personal reactions to it – and then encapsulate these personal reactions in a piece of music. His music of this kind is almost always about crafting his feelings about something, never a simple collage of impressions without deeply personal reflection.

But it’s difficult to be comprehensive about a force as huge as Debussy, and even this characterization limits an understanding of his work. His music is not just “about” something; it IS something in itself. It does not simply represent phenomena: it creates its own world. Debussy is also sometimes described as a Symbolist. The Symbolists were primarily a literary and poetic movement (although there were also Symbolist painters) who believed in the impossibility of directly stating Truth in art, and rather invested in the art object itself: the inherent qualities of the art are the Truth; not what the art is “about”.

There is nothing in Wagner as fleeting, as erotic, as trembling, as L’Apres-Midi or Jeux or the Chansons de Bilitis. Wagner only seems heavy-handed in comparison.

However futile our attempts are to summarize Debussy, the enduring power of his music speaks for itself, whether in well known works such as the orchestral L’Apres-Midi, La Mer, Iberia, or in less well known works. There is a mystery, an alchemy, at work in some of the piano Preludes and in the Images and Estampes, which eludes definition.

Occasionally I find myself somberly reflecting on the manner of his death – painful cancer, in earshot from his deathbed of the German guns pounding away at his beloved Paris. Such a contrast with his life, a life spent putting so much beauty into the world.